A Collapse: Credit Suisse

- Credit Suisse and its acquisition by UBS has tested the effectiveness of regulations and crisis management in the financial sector.

- The consolidation of Credit Suisse and UBS poses potential risks to global financial stability.

By William Willis and Michael Manners

The collapse of Credit Suisse, followed by its acquisition by UBS, stands as a significant event that has tested the resilience of banking regulations and the effectiveness of crisis management in the financial sector. This article explores the timeline of events and examines the implications for Switzerland as a financial centre and financial regulation as a whole.

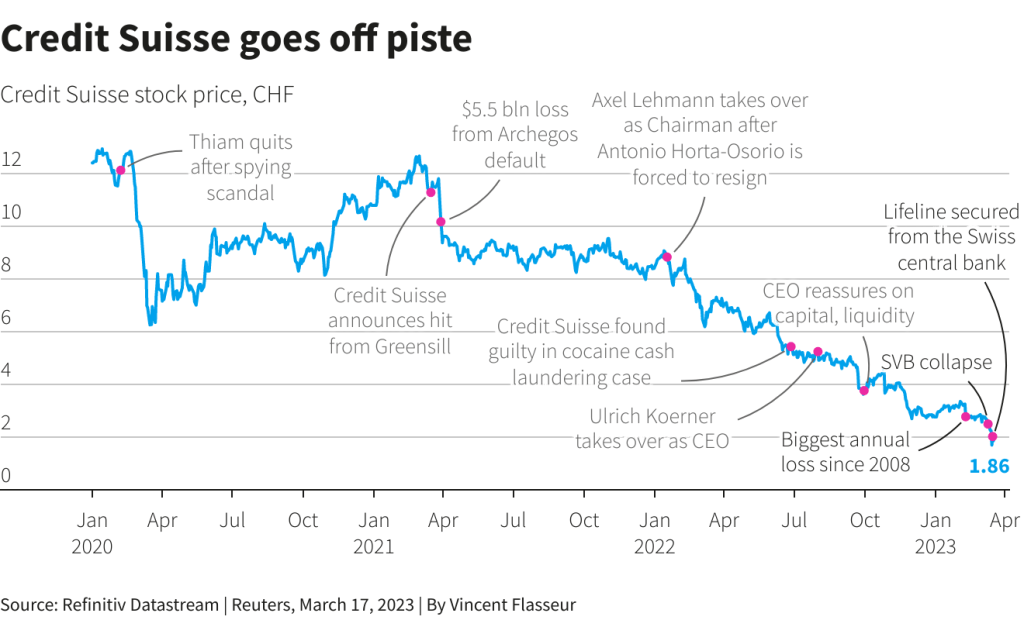

The troubles for Credit Suisse began with a series of scandals over the past two decades, eroding the bank’s financial position and tarnishing its reputation. However, it was a rumour began in 2022, suggesting that a major investment bank was in shaky territory that intensified speculations about Credit Suisse’s stability. The ensuing panic led to deposit withdrawals exceeding 100 billion CHF and a decline in the bank’s share price.

Despite regulatory reforms implemented after the global financial crisis, the collapse of Credit Suisse revealed shortcomings in the regulatory framework. The bank’s resolution plans, intended to facilitate a smooth resolution process, were incomplete despite years of preparation. This failure called into question the effectiveness of the reforms and raised concerns about the robustness of the regulatory structure.

Concurrently, while Credit Suisse’s stood on a fault-line, another tremor would further shake the banking world. Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), with $212 billion in assets, experienced a swift and dramatic failure, making it the largest lender to collapse since the global financial crisis. The bank’s heavy exposure to long-term bonds and its unhedged bet on low interest rates proved disastrous. As a result, SVB became insolvent or near-insolvent, leaving depositors, investors and the global banking system in a precarious position.

To bolster confidence and stabilise the situation, the Swiss National Bank provided Credit Suisse with a liquidity backstop of 50 billion, while the Swiss government granted guarantees for potential losses. When faced with a failing bank, various options are available. Insolvency was not viable for a large, interconnected bank like Credit Suisse, as it would generate significant uncertainty and take too long to wind up. Nationalisation was ruled out, partially due to public sentiment following the state’s rescue of UBS during the global financial crisis.

Amidst the limited choices, a merger with UBS emerged as the preferred option. Swiss authorities reportedly committed to this buyout as early as March 15. UBS negotiated a favourable deal, acquiring Credit Suisse for 3 billion CHF, a fraction of its previous peak valuation. The merger created a combined bank with $5 trillion of invested assets, but it also raised questions about fairness and taxpayer exposure.

One notable aspect of the deal was the wipeout of 17 billion Swiss francs of Credit Suisse’s alternative tier 1 (AT1) bonds. This controversial bail-in aimed to strengthen UBS’s capital position but invited scrutiny and further examination.

The collapse of Credit Suisse and subsequent buyout by UBS highlight critical questions for Switzerland as a financial centre and financial regulation in general. The consolidation of two major Swiss banks into a single entity concentrates a significant amount of assets and liabilities in one institution, which could increase risks if UBS were to face financial distress. UBS is considered a globally systemic important bank, meaning its failure could have far-reaching consequences due to its interconnectedness with other financial institutions.

The implications of this episode extend beyond Switzerland, if UBS were to collapse, it could trigger a domino effect, spreading financial stress to other banks and causing market turmoil. This potential contagion and systemic risk would likely have implications for the stability of the global financial market. Ultimately, this serves as a cautionary tale of the ongoing need for robust and adaptable financial regulations to protect stakeholders, maintain stability, and restore trust in the banking sector.