Japan’s Demographic Decline: The Labour Market Perspective

- The declining prime-age population is negatively affecting economic output, and productivity.

- Japan faces significant challenges in addressing the economic and social implications of its demographic decline.

- Japan’s population is shrinking due to low birth rates and cultural norms.

By Yassa Ahmed

Japan has seen its population decline over the past decade, as a result of declining birth rates and increasing life expectancy. This has had a profound impact on their economy and society. Cultural factors, economic liberalisation, and societal changes have contributed to this demographic shift.

The question of how this demographic transition manifested is not the main focus of this article, per say, as much robust work has already been done examining this. But we are looking to explore how the shrinking population affects Japan’s labour market, economic activity, and productivity.

By examining the challenges and opportunities a declining population presents, we aim to better understand the potential consequences for a consumer-driven, high-income economy like Japan.

Consumption drives production, that is the oldest song sung of capitalism, “consumption is the sole end and purpose of all production,” Adam Smith goes on to say. The want for individuals to sustain their lives, both as a necessity and for luxuries, creates industry to fulfil that need.

As consumption grows so does the economic activity that stems from it. Reflecting on this, the prime age population (PAP); employed peoples as those between 15-65 who (in the case of the above graph) have worked in gainful employment at least one hour in the past week or had a job but were absent, sets out our first area to note.

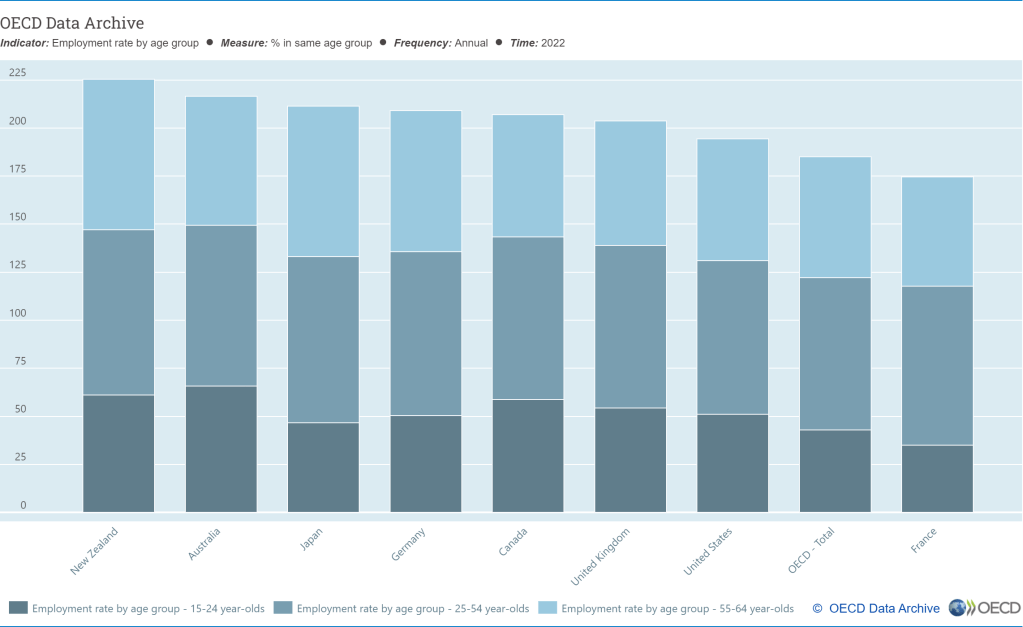

As the impact of a growing PAP is demonstrated in the increase in economic activity through stronger consumption yields from people, mostly by the labour force. This is interesting given that OECD data shows that employment is not concurrent across age groups. Particularly for Japan, as we see there is a lower bottom end and a larger top end compared to most OECD countries.

What this lays out in our heads is 2 questions: why 46% of young Japanese workers entering the labour market is one of the lowest, and why 78% of those passing the peak of their career and approaching retirement is one of the highest in the OECD?

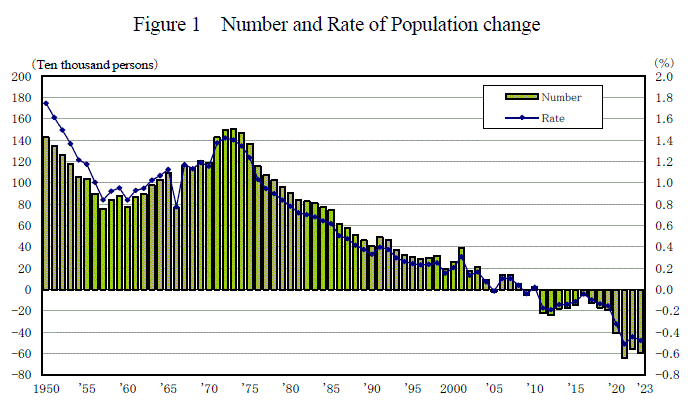

Japan’s demographic trajectory has been on decline for years, the countries population has continued to fall for the 13th year in a row. With a considerably low birth rate of 1.26 births per woman, the median age in Japan has increased to a high of 49.

This shift has been advanced by a decline in marriages, as 27.2% of men and 20.4% of women between 30-34, surveyed, showed the life intention to marry among never-married persons increased since previous surveys. Disinterest in civil unions has progressed particularly as societal norms change in favour of a more inclusive labour market for women.

Women in Japan, like men, are expected to work long hours to get a head. However, in the case of female labour force participation, it is considerably more challenged by other women witnessing female peers encountering ‘promotional delays after marriage and childbirth’ as the IMF found. Females serve to benefit from a far greater exposure to the job market but so does the incentive to build their careers on an even footing with men.

A combination of these domestic woes for Japan explains why there are and will be fewer and fewer Japanese, as the rate of decrease was 0.48%, greying the hair of many. The ageing PAP is expected to have substantial implications for the economy and labour market.

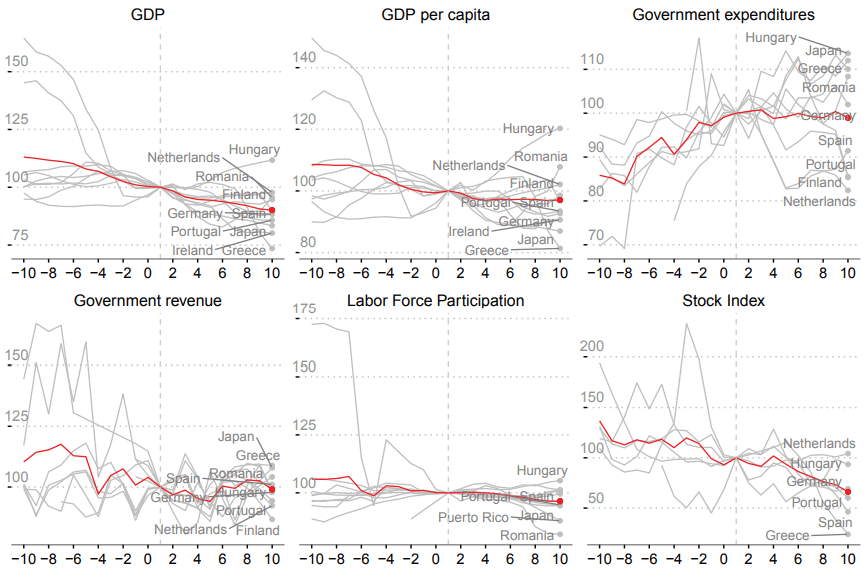

These graphs from the Center for Global Development (CGD) present a varied spread of datasets generally over 80 years. We can assess the productivity of the labour market, as it begins to be impacted by negative prime-age populations. GDP stays high as the proportion of PAP continues to grow, but we can observe a steep decline as negative PAP growth becomes more pronounced for Japan.

In general, high-income countries during periods of negative population growth saw a 1.4% annual GDP growth rate. Demonstrating a lower economic outcome for most countries with a negative PAP. Turning to the general welfare and standard of living of people, GDP per capita follows this outlook of a regressive trend.

A negative PAP growth sees a heavy decline in economic output per person for Tokyo, but the study also finds a younger working-age population may be associated with a rising labour share of income. Meaning a younger working age population could potentially lead to a higher share of income going to workers.

But the complete picture sees government revenue declining over time as government expenditure continues to climb. The actual labour force, obviously, is decreasing as the negative prime age population growth continues. This similar process lastly impacts labour-intensive industries, which is associated with this lower stock market return.

Research done by the Center draws weight to a less favourable economic environment, younger workers stand to be impacted the hardest regardless of gender. Fewer taxpayers to support an ageing population will see tax and insurance premium revenue decrease by 10% in 2040.

Politically Japan has already begun to remedy this demographic transition through policy. Last year Japan’s government pushed out $26 billion for new child care measures. While foreign migration increased 11% to be 3 million for the first time. A positive avenue for change, but one that will need to outmatch the rate of a shrinking population.

Having new working-age citizens naturally takes 15-24 years, which may have you wondering about the stability of the labour market. Mitigation strategies aside, CGD did show us that worries around PAP are not just a Japanese issue, but is one impacting a decent slice of high-income and upper-middle-income countries.

Korea is one to keep your eye on as it trails very closely to its East Asian neighbour. The learns we can take out of the Japanese story is a developing one, but we can be certain that the global economy is faced with more challenges in the future. One that sees countries being wary of growing richer as they could also be growing older.