UK Housing Crisis: The Benefits of Commercial Conversions?

(5 minute read)

- The housing crisis is primarily concentrated in urban areas.

- Factors like limited land supply, restrictive planning regulations, and rising housing costs have affected the nation.

- Converting commercial property into residential housing is a potential solution to address the housing shortage.

By William Willis and Michael Manners

The conversation around housing has become increasingly sorrowful, with many Brits in their late 20s to early 30s accepting a belief that they will never stop renting or be able to find stable housing for the future. As migration and mobility add to a divisive debate about the effects on the supply of housing, and the potential blame game that ensues, understanding the provisions of a housing crisis in an increasingly urbanised world is a beneficial one to have.

For this article, we want to explore these growing concerns and inspect how accessing affordable housing through legislative change, can encourage a greater supply of dwellings. Particularly through the conversion of commercial property to residential property, and assess the effectiveness it will have in boosting the British housing supply.

Steady Move to Urbanisation

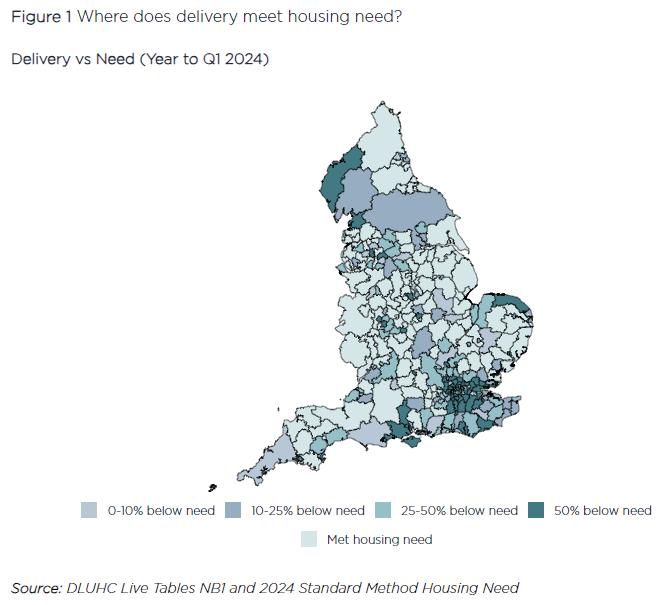

Understanding the housing crisis starts with dispelling a distortion of information. The supply of residential property is a very specific problem focused on urbanised areas, it is not necessarily one affecting every part of Great Britain. Looking at just England, we can see where housing need is met or below required levels. Large clusters form around areas in Greater Manchester, Norfolk, Dorset, West Sussex, East Sussex, Surrey and of course Greater London.

These areas are expected to be in higher demand of housing, because demographic migration is deeply attracted to residential land near jobs and services, hence the creation and maintenance of urbanised centres. Increasing urbanised settlement has been spread by net internal migration of young peoples’ between the ages of 17-20 from predominantly rural areas to urban areas, accounting for about 30 to 40,000 between 2011 to 2020.

However, net internal migration as a whole has contributed oppositely to favour rural areas by most age groups. Long-term immigration found inflows of roughly 30% over the period of 1990 to 2019 by non-UK citizens favouring London. The next highest being 15% of immigrants favouring the South East region in the same time frame. Indeed, urban areas seem to be favoured more by foreign peoples’, as immigrants are attracted to urban environments as they value their ability to gain higher wages in a city. According to the 2021 census, 40% of London residents were born abroad.

Historical Levels of Supply Decline

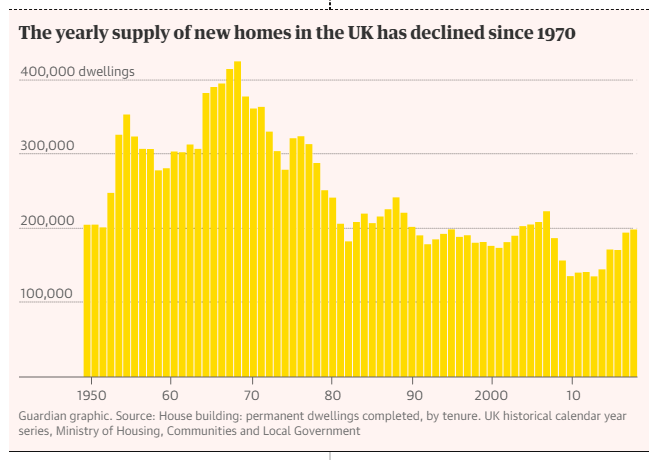

Supply problems have persisted since new builds peaked in the 1970s. They began to decline as a result of planning systems designed to restrict the growth of large cities by giving local authorities powers to block new developments and creating an unusually unpredictable decision-making process. A restrictive planning system meant the land needed to supply public and private housebuilding was being reduced, even though interest for homeownership was being supported by the government.

The introduction of the ‘right to buy’ in the 80s enabled the conversion of social housing into private housing, as tenants were encouraged to buy their homes outright, curtailing local councils’ from their own supply of public housing, denting their communities’ social housing. Wider access to mortgages grew in the following period, while wages unfortunately started to depress from a 29% high growth rate to 2.5% in 1993.

As income became disconnected from housing, between 1983 to 2010s, the housing market was affected by significant housing market crashes that saw a mixture of repossessions rise, and the shift of homeownership to higher-income earners who could afford to weather the financial storm. Currently, the affordability ratio of purchasing homes to earnings is 8.28; £33,208 is the median salary and the median house price is £275,000. To further exacerbate the affordability of housing, more adults are on average opting for a smaller household size, increasing the number of households that are set to rise to 23.2 million by 2043.

Converting Commercial Property to Residential

“There is a desperate need for more affordable housing, this is disproportionately impacting low income households,” as the Joint Inquiry into Rethinking Commercial to Residential Conversions states. The group investigated and found that over 100,000 households have had to move into temporary housing due to the unaffordability in England. With another 1.2 million on a waiting list to enter social housing, a greater need to help communities avoid homelessness has arisen.

We mentioned before how a lack of land usage, at a point in the UK’s history, caused restrictive measures stagnating housing growth. The hope of this innovative solution is to meet demand by unlocking land use in the short-term through repurposing underutilised commercial properties and turning them into residential homes. However, previous conversions have been undertaken by a process that did not require developers to submit a full planning application, which had led to “the worst examples of homes that we have seen” said the group.

This new approach wants to priorities the private members’ bill of Vicky Ford (former MP of Chelmsford) to apply an affordable housing obligation to conversions of commercial property. The inquiry advocates for the introduction of a dedicated funding pool to empower the conversions, strengthen standards to ensure transformed properties adhere to secure and habitable homes, and allow local government greater oversight into where the conversions happen and to set affordable housing requirements to meet local needs. Vicky Ford stated that, ‘if the same affordable housing percentages were applied to commercial conversion, that are applied to new builds, this could have released 453 new affordable homes in her constituency alone.’

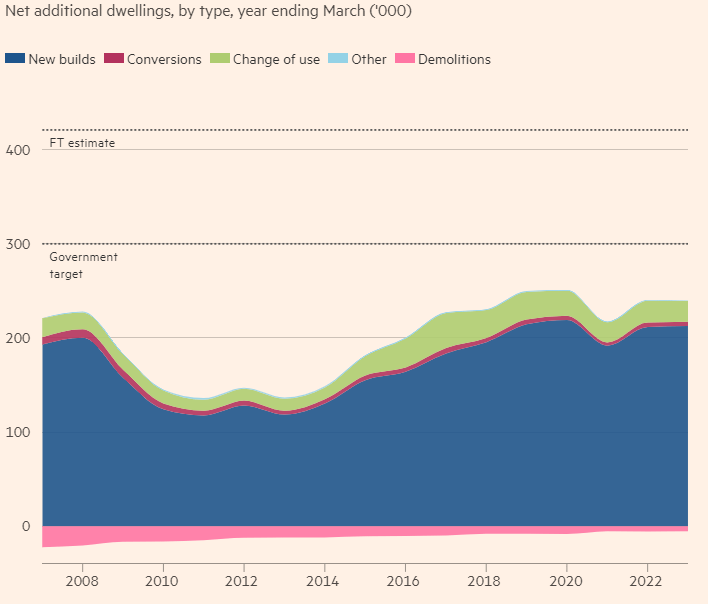

The government set an ambitious target of new dwellings a year at 240,000 in 2004 and a revised amount in 2018 of 300,000, which has in the last 2 decades not been met. The financial times views, the government target as potentially undercounted, as determining housing needs depends on the pace at which people move in their own homes. Conversions so far have amounted to a sliver of total dwelling creation, and this project may provide a quick and partial solution to the gap in demand and supply of affordable housing.

Will Commercial Spaces Only be a Band-Aid?

Urbanisation has been met with a growing population flow of both immigration and rural movement into big cities. This has dampened, in part, access to dwellings for Brits in those areas. However, the seeds of trouble for housing had already been laid in the post-war period. Regulation on land and the reduction in social housing due to the liberalisation of the Thatcher era, saw the government encourage private ownership of one’s home and deflate local governments’ access to their community housing share.

Furthermore, declining wages and changing attitudes to the makeup of households in the UK, depressed personal interest in access to the housing supply, as well as, the rising cost of residential properties. In this way, we can see that the problem is twofold, in that, affordable housing has become inaccessible due to a condensed social housing supply and residential property becoming out of reach for low-income earners.

The Affordable Housing (Conversion of Commercial Property) Bill and inquiry made, sheds light on a solution that can support local government in providing better affordable housing, yet, it has only passed the first reading (with unanimous support). Nonetheless, it may well be a small plaster that is trying to aid a large wound, so more work will have to be seen by policy makers in parliament.